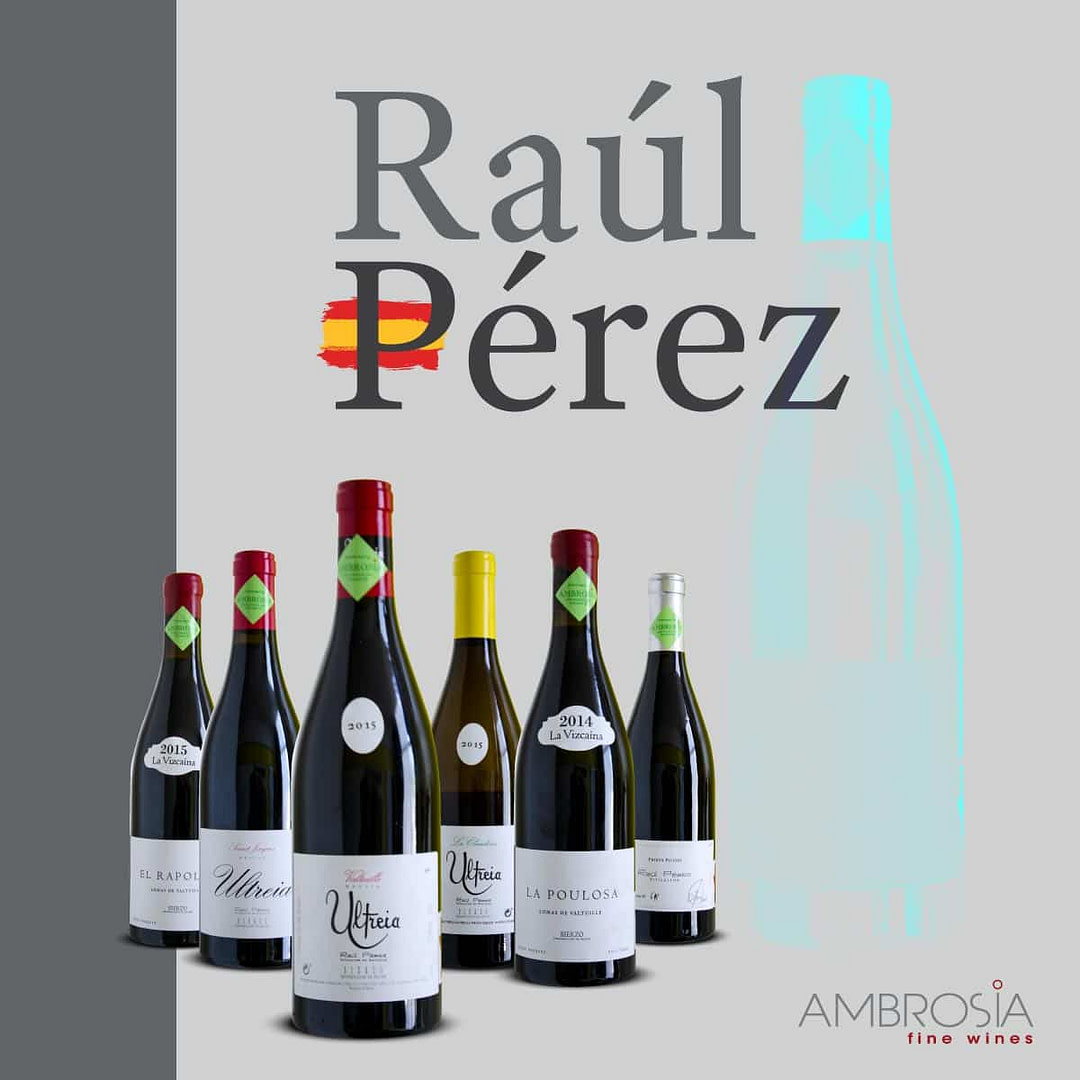

Matt Kramer Wine Spectator Issue: June 30, 2018

VALTUILLE DE ABAJO, Spain—I remember vividly the first time I drank a wine from Raúl Pérez. Oddly—and, I admit, unprofessionally—I don’t remember exactly which wine of his it was. There’s a reason for that, which I’ll get to in a moment.

More importantly, the reason the memory is so vivid is that the experience of it was almost electric. It gave a thrill, one charged with an insistent inquisition: What is this wine? All I knew was that it was from Bierzo, a Spanish wine district which at the time meant little to me.

That first impression was conflicted and contradictory: The wine was like a Burgundy/not Burgundy, which is to say that it was powerfully reminiscent of a beautiful, soil-suffused Pinot Noir, yet it was too rich, too dense and not quite delicate enough to be a Pinot Noir, from Burgundy or anywhere else. So, scratch that. Maybe it was a Syrah?

Bierzo is a long-neglected, ancient Spanish wine zone in the northwestern corner of the country, smack on the pilgrim’s path to Santiago de Compostela. This latter feature helps explain Bierzo’s signature red grape, Mencía. The thinking is that various pilgrims brought vine cuttings as “house presents” while staying at one or another of the Cistercian monasteries long-extant in Bierzo. (We now know from DNA testing that Mencía is the same as the Portuguese grape Jaen do Dão.)

Yet Bierzo wine—as well as wine from neighboring Ribeira Sacra, where Mencía is also the informing grape—is only rarely entirely Mencía, never mind what the label says. This is especially true for vineyards with vines that are a half-century to a full century old. Bierzo is chockablock with such old vineyards, all head-trained and pruned low to the ground.

“All of these old vineyards are really mixtures, what you would call a field blend,” says Raúl Pérez. “And, honestly, we don’t know precisely what’s in these vineyards. Mencía for sure. But also Alicante Bouschet, Brancellao, Caiño and Trousseau or Merenzao. And some white grapes too!” He laughs, “So we just call it Mencía and that’s that.”

But what Pérez does with these grapes is, if not unique to him (though it very well may be, so individualistic he is), surely like few others anywhere, including in Bierzo itself. Although Pérez was academically trained as a winemaker, he’s thrown his formal education out the window.

I mean, do you know of another winemaker whose red wine technique is to put all of his grapes together in a large vat as whole, uncrushed clusters, which means with all of the stems attached, and leave the fermented juice with the skins for five months before racking off the wine into small, older oak barrels? (Modern winemaking typically employs just two to three weeks of skin contact.)

Once the red wines are in barrel, Pérez then purposely fills each barrel only three-quarters or so full, rather than the nearly universal approach of filling the barrel completely full to preclude unwanted oxidation and then keeping it full as the wine evaporates by topping it off with additional wine. But Pérez doesn’t “top off” his barrels.

Why does he do this? Because he wants to encourage the growth of a surface-dwelling yeast culture the Spanish call flor, or flower. Famous in Sherry-making, the encouragement of flor for red wines is, as best as I know, simply not done.

“It works fine,” says Pérez. “The flor protects the wine from oxidation. And it doesn’t add any flavors. And it prevents that volatile acidity you were asking about.”

And why, you ask, couldn’t I recall precisely which wine I first tasted that made me want to meet Raúl Pérez? It’s because Pérez is constantly issuing a stream of small-production wines, both reds and whites, from not just numerous single vineyards in Bierzo, but also from Ribeira Sacra and half a dozen other regions in Spain—and from Portugal’s Douro zone as well. He’s only 47 years old and he’s already “fathered” nearly 100 different wines over the years.

Simply being Raúl Pérez is a full-time job. Making some of Spain’s finest and most intriguing reds (and whites too) is just the byproduct.

Matt Kramer has contributed to Wine Spectator regularly since 1985.